VProg Intro : Week 3, Binary Search - Solutions

HW1: Successful Pairs of Spells and Potions

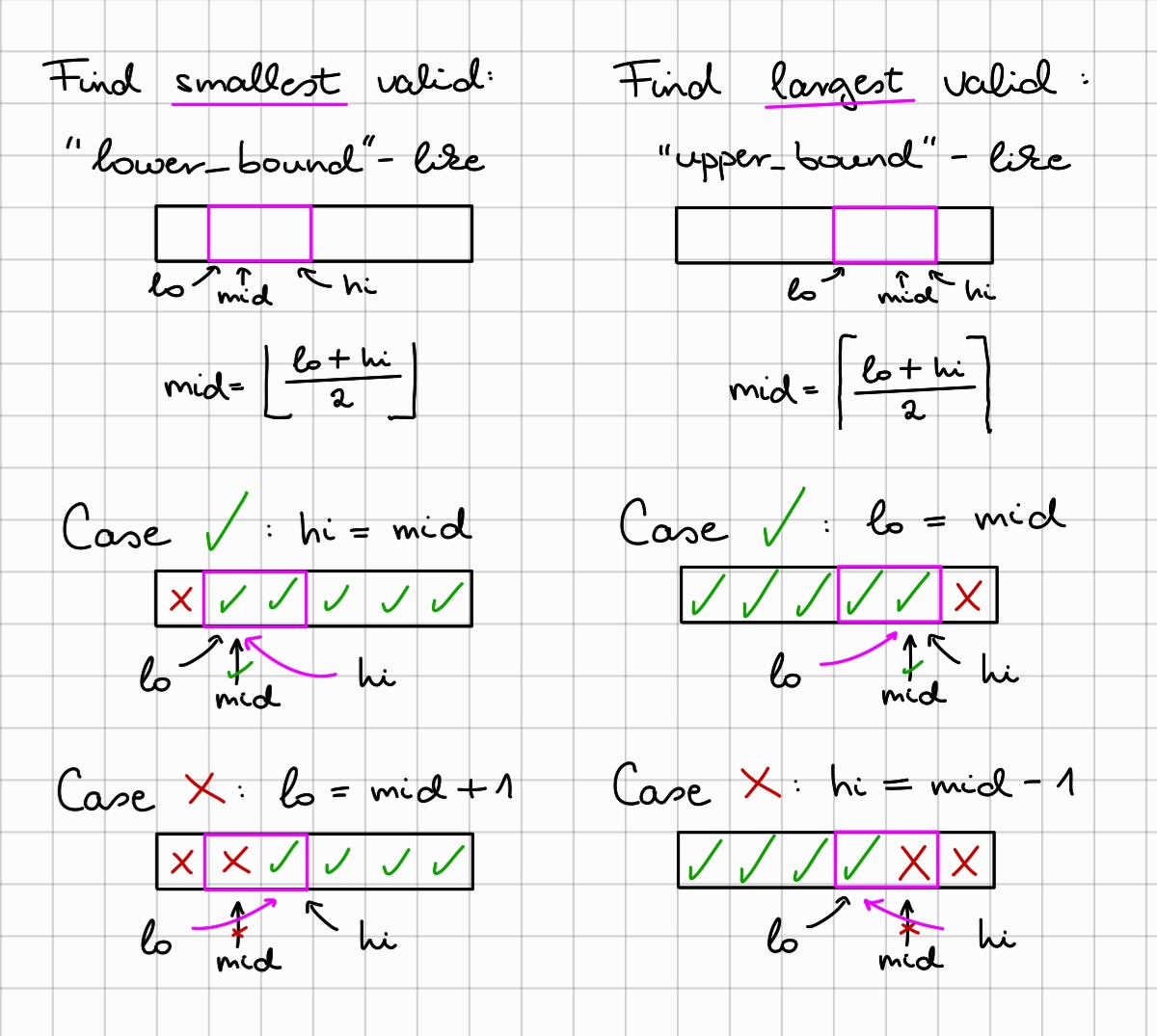

For each spell, we are looking for the number of potions that will form a successful pair with it. We can first order the potions by increasing strength. Then, for each spell we can perform a binary search on the sorted potions array, looking for the smallest strength potion, that will still succeed, when paired with that spell. Then, any potion stronger than this will also succeed, while anything weaker will fail. So we can count the number of potions on the right side of the minimal successful one.

You can implement the binary search by hand in the following way:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

using ll = long long;

class Solution {

public:

bool successful(ll spell, ll potion, ll success) { return success <= spell * potion; }

vector<int> successfulPairs(vector<int>& spells, vector<int>& potions, ll success)

{

std::sort(potions.begin(), potions.end());

std::vector<int> ans;

for(auto& spell : spells)

{

int lo = 0;

int hi = potions.size();

while(lo < hi)

{

int mid = (hi-lo)/2 + lo;

if (successful(spell, potions[mid], success))

hi = mid;

else

lo = mid + 1;

}

ans.push_back(potions.size()-lo);

}

return ans;

}

};

Or in this case, since the potions array is already ‘materialized’ in the memory, you can use std::lower_bound too.

In c++, when we have integers int x,y;, if we write x/y, that will be an integer division and return the floor, $\lfloor \frac{x}{y} \rfloor$. A neat trick to get the ceil, $\lceil \frac{x}{y} \rceil$ instead, is to write (x+y-1)/y. This works, since (x+y)/y would always increase the result by +1, so (x+y-1)/y increases by +1 only when the remainder of x mod y is not 0.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

using ll = long long;

class Solution {

public:

vector<int> successfulPairs(vector<int>& spells, vector<int>& potions, ll success)

{

std::sort(potions.begin(), potions.end());

std::vector<int> ans;

for(auto& spell : spells)

{

ll minpotion = (success+spell-1)/spell;

int count = potions.end() - lower_bound(potions.begin(), potions.end(), minpotion);

ans.push_back(count);

}

return ans;

}

};

HW2 : Koko eating bananas

This is a typical ‘binary search for the smallest possible solution’ type of task. To see this, you have to answer two questions:

- Can you validate a solution? - If someone gave you a speed, could you check if Koko would finish in time with that speed?

- Is the solution space ordered? - If a specific speed is correct, would any higher speed work also?

The answer is yes to both questions, so let’s do a binary search!

We need a starting interval of possible answers. The lowest possible correct answer would be a speed of 1 banana / hour, so we set this as lo. The highest possible speed we may need is for Koko to ‘devour’ each pile in 1 hour (she cannot go faster than that), so that would mean she needs to be able to eat the largest pile in 1 hour, so we set hi to this amonut of bananas / hour.

Then, we have a checker function can_finish, which tells us if a specific speed is enough for Koko to finish in time.

The rest is binary search, as seen before. :)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

using ll = long long;

class Solution

{

public:

bool can_finish(const vector<int>& piles, int hours, const int speed)

{

for(auto& pile : piles) hours -= (pile + speed - 1) / speed;

return 0 <= hours;

}

int minEatingSpeed(vector<int>& piles, int h)

{

int lo = 1;

int hi = *max_element(piles.begin(), piles.end());

while(lo < hi)

{

int mid = (hi-lo)/2 + lo;

if (can_finish(piles, h, mid))

hi = mid;

else

lo = mid + 1;

}

return lo;

}

};

HW3 : Cardboard for Pictures

In many cases, exercises where a binary search is possible also allow for direct solutions. This exercise is one of those. The question is, would you rather implement a quadratic solver on floating point numbers or a binary search on integers?

The correct answer is the latter, so let’s look at binary search first.

Binary search

To implement the checking function bool fits(ll w), we must pay attention to overflows. Before executing any operation, we check if the operation would result in an overflow, without actually executing it!

For this, we store the maximum value of long long, in maxll and the maximum value we can square and still fit, in maxllsql.

To check if side * side would result in an overflow, we check if (maxllsq < side). To check if total + add would result in an overflow, we check if (maxll - add < total).

A possible upper bound on the valid w’s is $\sqrt{\frac{c}{n}}$, which would happen when all $n$ pictures were size $0$.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

using ll = long long;

const ll maxll = numeric_limits<ll>::max();

const ll maxllsq = sqrt(maxll);

ll n, c;

vector<ll> p;

bool fits(ll w)

{

ll total = 0;

for(auto& px : p)

{

ll side = px + 2 * w; if (maxllsq < side) return false;

ll add = side * side; if (maxll - add < total) return false;

total += add; if (c < total) return false;

}

return true;

}

int main()

{

int t; cin>>t; while(t--)

{

cin >> n >> c;

p.assign(n, {}); for(auto& px : p) cin>>px;

ll lo = 1;

ll hi = sqrt(c/n);

while (lo < hi)

{

ll mid = (hi - lo + 1)/2 + lo;

if (fits(mid))

lo = mid;

else

hi = mid - 1;

}

cout << lo << endl;

}

}

Since are searching for the largest frame width for which we still have enough cardboard. This makes our binary search implementation slightly different here. In this case, we implement upper_bound, as opposed to lower_bound.

It is useful to think about what will happen when our interval shrinks to size 2, this is where we can accurately set the +1/-1’s in our equations.

Direct implementation - A numerically stable quadratic formula

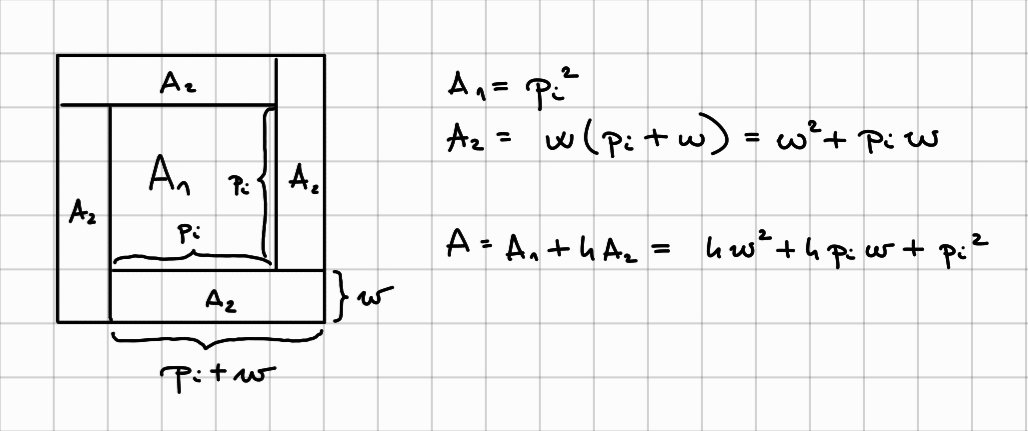

For a specific $w$, the amount of cardboard we are using for a picture of size $p_i$ can be calculated as follows:

The total amount of cardboard should be $c$, therefore our equation is

\[4n\cdot{}w^2 + (4\sum\limits_{i=1}^{n} p_i)\cdot{}w + p_i^2 = c\], which we need to solve for $w$.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

using ll = long long;

// solve ax^2 + bx + c = 0

const double eps = 1e-14;

vector<double> quadsolve(double a, double b, double c)

{

if(abs(a) < eps) // linear

{

if(abs(b) < eps) return {}; // c = 0

return {-c/b}; // bx + c = 0

}

double D = b*b - 4*a*c; // discriminant

if (D < -eps) return {}; // no real roots

if (abs(D) < eps) return {-0.5*b/a}; // double root

// numerically stable: no catastrophic cancellation

double sgnb = (b >= 0.0) ? 1.0 : -1.0;

double q = -0.5 * (b + sgnb * sqrt(D));

return {q/a, c/q};

}

int main()

{

int t; cin>>t; while(t--)

{

ll n, c; cin >> n >> c;

vector<ll> p(n); for(ll &px : p) cin >> px;

ll A=4*n, B=0, C=-c;

for(auto& px : p) { B += 4*px; C += px*px; }

auto result = quadsolve(A,B,C);

auto ans = *max_element(result.begin(), result.end());

cout << (ll)round(ans) << endl;

}

return 0;

}

The vector<double> quadsolve(double a, double b, double c) function above finds the roots of the quadratic formula $ax^2 + bx + c = 0$. Mathematically, the roots are given by

, where $D = b^2 - 4ac$ is the discriminant.

There are two important implementation details in this code:

Firstly, we must always allow for some numerical precision error. So we set $\varepsilon = 10^{-14}$ and consider a variable $x$ to be $0$ whenever $x \in [-\varepsilon, \varepsilon]$, and to be negative or positive only outside of this interval.

Secondly, there is one numerical stability issue in the quadratic equation: if the value of $\sqrt{D}$ is close to $|b|$, then one of the two possible values of $b \pm \sqrt{D}$ can be too small, which results in catastrophic cancellation of the terms - a loss of significance during our calculations.

The implementation above avoids this issue by calculating the value which does not suffer from this issue and using Vieta’s formula $x_1 \cdot x_2 = \frac{c}{a}$ to find the value of the other.

For more details, see the PTVF Numerical recipes book, equations 5.6.4, 5.6.5 in the 2nd edition.

Challenge: Doremy’s IQ

For this exercise, we first have to make one important observation:

If we want to take a contest that would lower our IQ, it is always better to choose a later one, so we have a higher IQ for the contests in the days in-between the two options.

More formally, given any solution to this problem, we can create another solution with the same amount of contests taken by copying all contests that did not lower our IQ, then picking the latest possible contests from the remaining ones to match the total number of contests needed.

Since any IQ-lowering contest would move to a later date, our daily current IQ could only increase, which means we can test the same contests in-between without losing IQ.

We can recall, that this is a ‘greedy-stays-ahead’ type of proof, similar to the Chat room problem from Week 1.

This means that a good strategy for us is to first start taking contests that don’t lower our IQ, then at a certain day switch to taking all remaining contests.

The question is: At which day should we change our strategy?

We want to pick the earliest day, that is still viable, so that we don’t end up with negative IQ at the end. We can simply simulate this process in $O(n)$ and check our remaining IQ at the end.

If a strategy-changing day is viable, then every later day is also viable. To maximize the contests we took, we want to find the earliest viable day. This allows us to binary search for its location!

We will execute $O(log(n))$ steps during our binary search, each step being an $O(n)$ simulation, for a total of $O(nlog(n))$, which fits into out time limits!

A possible implementation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

int n, q;

vector<int> a;

bool doremy_result(int from, vector<int>& ans)

{

ans.assign(n, {});

int q_left = q;

for(int i=0; i<from; ++i)

{

ans[i] = (a[i] <= q_left);

}

for(int i=from; i<n; ++i)

{

ans[i] = !!q_left;

q_left -= (q_left < a[i]);

}

return 0 <= q_left;

}

int main()

{

ios::sync_with_stdio(0); cin.tie(0);

int t; cin>>t; while(t--)

{

cin>>n>>q;

a.assign(n, {}); for(auto& ax: a) cin>>ax;

vector<int> ans;

int lo=0;

int hi=n;

while (lo<hi)

{

int mid = (hi-lo)/2 + lo;

if (doremy_result(mid, ans))

hi = mid;

else

lo = mid+1;

}

doremy_result(lo, ans);

for(int i=0; i<n; ++i) cout << ans[i];

cout << endl;

}

return 0;

}

Going backwards

Sometimes, thinking about a problem in reverse can make it easier to solve. Imagine starting on the last day with an IQ of 0 and moving backwards in time. We can simulate the process in reverse like this:

- While our current IQ is less than our original starting IQ, we attempt all contests.

- Each time we try a contest that is harder than our current IQ level, our IQ increases.

- We can keep increasing our IQ until we reach our starting IQ.

- Once we’ve reached our starting IQ, we can only attempt contests that are not more difficult than our IQ.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

int main() {

int t; cin>>t; while(t--)

{

int n, q; cin>>n>>q;

vector<int> a(n); for(auto& ax: a) cin>>ax;

vector<int> ans(n);

int q_curr = 0;

for(int i=n-1; 0<=i; --i)

{

if (a[i] <= q_curr) ans[i] = 1;

else if (q_curr < q)

{

ans[i] = 1;

++q_curr;

}

}

for(auto& ansx: ans) cout<<ansx;

cout<<endl;

}

return 0;

}

You may have noticed that there is a tiny discrepancy here: If the difficulty of a contest is $x$ and our current IQ is $x-1$, we would be increasing it, which means our IQ was $x$ before testing, in which case we should not have lost IQ testing that contest. Luckily, this only happens when the optimal solution allows for some IQ left over at the end. For example, when n=3, q=3, a=[4,3,3,3], the optimal solution is ans=[0,1,1,1], which leaves us with $1$ IQ at the end.