VProg Intro : Week 1, Introduction - Solutions

HW1: Present from Lena

There are many ways you can come up with code for this.

In this example, we calculate the following way:

- Iterate each cell position in the $(2n+1) \times (2n+1)$ grid.

- For cell $(i,j)$, calculate its Manhattan-distance from the center cell $(n,n)$, via $\vert n-i \vert + \vert n-j \vert$.

- This distance determines the number placed in the cell, $x = n - \vert n-i \vert - \vert n-j \vert$.

- When $x$ would be negative, we print a space instead.

- Don’t forget to print all whitespaces in-between.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

int n; cin >> n;

int size = n * 2 + 1;

for(int i = 0; i < size; ++i)

{

for(int j = 0; j < size; ++j)

{

int x = n - abs(n - i) - abs(n - j);

if(x >= 0)

{

cout << x;

if(j < n || x != 0) cout << " ";

}

else if(j < n) cout << " ";

}

cout << endl;

}

}

HW2: Chat room

We can do a simple greedy algorithm: Iterate Vasya’s message and when we find the next matching character from the word “hello”, we mark it as done.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

string s; cin >> s;

string hello = "hello";

int i = 0;

for(char c : s)

{

if(i < hello.size() && c == hello[i])

++i;

}

cout << (i == hello.size() ? "YES" : "NO") << endl;

return 0;

}

Although we can see intuitively that this code is correct, for more complex greedy solutions, it might be good to know how to reason about their correctness with our teammates.

In this case we can formulate a so-called “Greedy Stays Ahead” argument.

If Vasya’s message contains the word “hello” as a substring, let’s say at indices $f_1, f_2, f_3, f_4$ and $f_5$, then the greedy algorithm will find a character ‘h’ at a position $g_1 \leq f_1 < f_2$.

Then, when looking for the character ‘e’, it will start checking from position $g_1+1 \leq f_2$, therefore it will find one at $g_2 \leq f_2$.

And so on…

If Vasya’s message does not contain the word “hello”, this algorithm will return “NO” as well.

You can read more about corretness proofs for greedy algorithms here.

HW3: We Were Both Children

The naive solution to this algorithm would look something like this:

We simply calculate for each coordinate how many frogs will land there eventually.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

int t; cin >> t; while(t--)

{

int n; cin >> n;

vector<int> s(n+1, 0);

for(int i=0; i<n; ++i)

{

int x; cin >> x;

for(int j=x; j<=n; j+=x) ++s[j];

}

cout << *max_element(s.begin(), s.end()) << endl;

}

return 0;

}

However, this results in a time limit exceeded. We have $n$ frogs for the outer for-loop and each frog can hop at most $n$ times, in the inner for-loop, so our algorithm is $O(n^2)$.

Roughly speaking, since $n \leq 2 \cdot 10^5$, an $O(n^2)$ algorithm would perform around $const \cdot 4 \cdot 10^{10}$ steps, however $10^7$ steps is roughly around $1$ second on these platforms, so we are way out of the 3 seconds/test case time limit stated in the exercise.

Intuitively, the biggest problems are caused by having too many frogs with relatively short hop-lengths, since this code spends the most time processing those, hop-by-hop. So, if we process them together, this will cut back tremendously on the runtime.

Therefore, we will count the frogs who have the same hop-length and process them together, like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

int t; cin >> t; while(t--)

{

int n; cin >> n;

map<int, int> a;

for(int i = 0; i < n; ++i)

{

int x; cin >> x;

++a[x];

}

vector<int> s(n + 1, 0);

for(auto x : a)

{

for(int i = x.first; i <= n; i += x.first)

s[i] += x.second;

}

cout << *max_element(s.begin(), s.end()) << endl;

}

return 0;

}

Mathematically, we can argue, that now the internal for-loop, processing the frogs with hop length $x$, will execute $\lfloor \frac{n}{x} \rfloor$ number of times, which accounts for a total of $\sum\limits_{x=1}^{n} \lfloor \frac{n}{x} \rfloor$ steps.

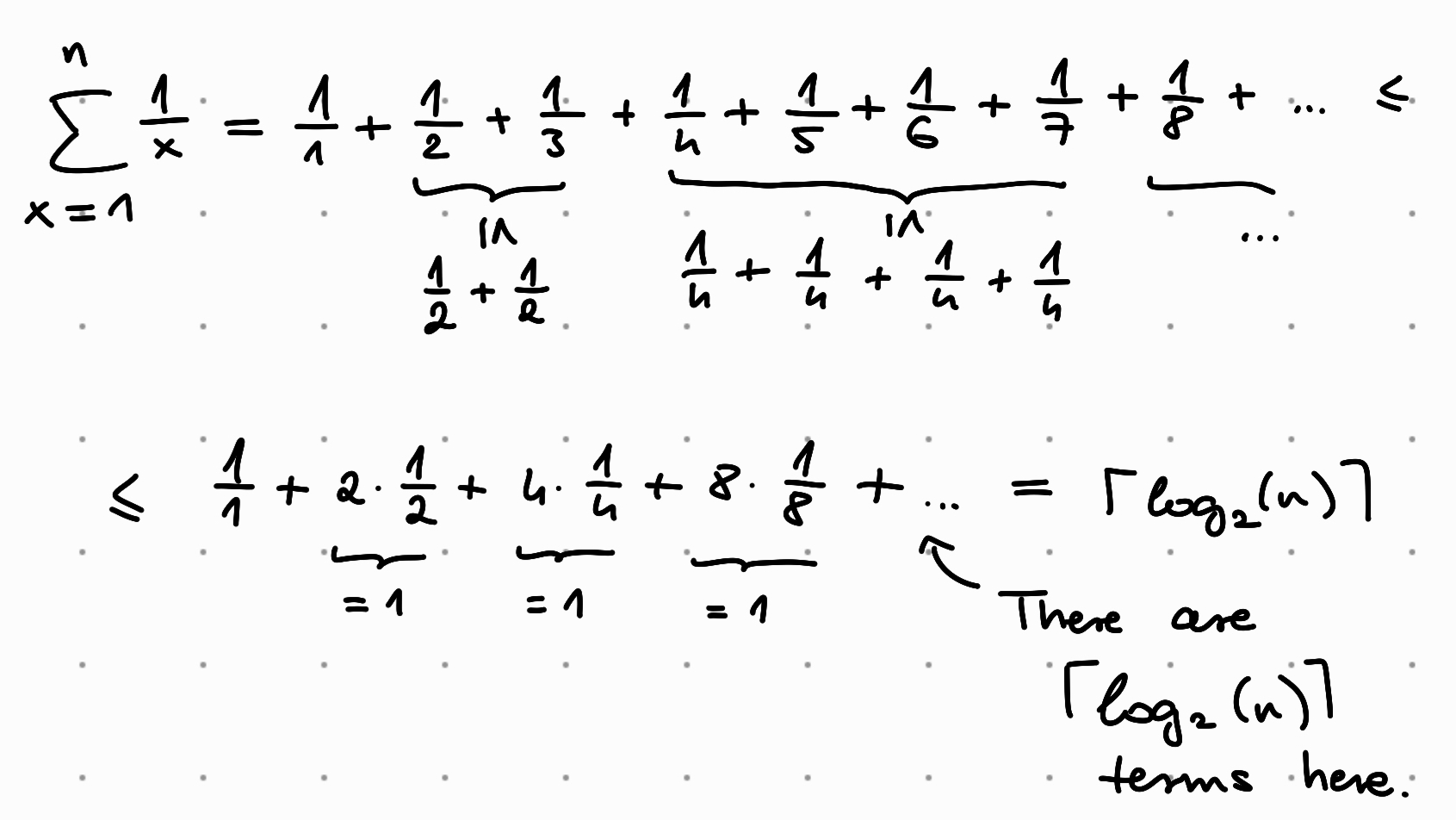

It is very useful to remember, that the sum of a harmonic sequence, $\sum\limits_{x=1}^{n}\frac{1}{x}$ is $O(log n)$. This is because we can upper-estimate each $\frac{1}{x}$ with the closest fraction that has a power of $2$, in the following way:

With similar logic $\sum\limits_{x=1}^{n} \lfloor \frac{n}{x} \rfloor$ is then $O(n \log n)$.

Using the same rough estimation as before, when $n \leq 2 \cdot 10^5$, then this algorithm runs in roughly $const \cdot 10^5 \cdot 5 \cdot \log_2(10)$ steps, which fits into the $3$ seconds time limit of the task.

Poor Pigs

We can quickly see that $r = \lfloor\frac{\text{minutesToTest}}{\text{minutesToDie}}\rfloor$ is the number of testing rounds we have available to us and forget about the minute parameters altogether.

When you have a task that is hard to solve, one trick you can do is to solve a simpler version of it first, then try to generalize that solution. In this case, let’s first think about what the solution is for $r = 1$.

For $n$ buckets, how many pigs should we request, so that we can tell exactly which bucket is poisonous?

- For $n=1$, we don’t need any pigs.

- For $n=2$, one pig suffices, since we give one bucket to the pig, if it dies, that was the poison, otherwise it was in the other bucket.

- For $n=3$, one pig is not enough, but we can do with two, one bucket to each and not giving the third bucket to any of them.

- For $n=4$, two pigs are enough, since we can give, let’s say the first bucket to both pigs, the second bucket to the first pig, the third bucket to the second pig and the fourth bucket to neither. In all cases, the pattern of dead pigs will tell us which was the correct bucket.

You can think about the pigs as 0/1 bit strings: 0 represents a pig that didn’t die and 1 represents a pig that died. Then the outcome is a number in binary format, where each pig corresponds to a certain bit position. For $k$ pigs, let’s number these pigs/bit positions from $0$ to $k-1$. We will also number our buckets, from $0$ to $n-1$ and represent them as binary numbers: where they contain a one, we feed them to the corresponding pig. Then, we can read the number of the poisonous bucket from the resulting deaths.

For example, for $n=8$:

- Bucket $0 = 000_{2}$: Don’t give this bucket to any pigs. If no pigs die, this has the poison.

- Bucket $1 = 001_{2}$: Give this bucket to pig $0$. If only pig $0$ dies, this has the poison.

- Bucket $2 = 010_{2}$: Give this bucket to pig $1$. If only pig $1$ dies, this has the poison.

- Bucket $3 = 011_{2}$: Give this bucket to pig $0$ and $1$. If exactly pig $0$ and $1$ die, this has the poison.

- Bucket $4 = 100_{2}$: Give this bucket to pig $1$. If only pig $1$ dies, this has the poison.

- Bucket $5 = 101_{2}$: Give this bucket to pig $0$ and $2$. If exactly pig $0$ and $1$ die, this has the poison.

- Bucket $6 = 110_{2}$: Give this bucket to pig $1$ and $2$. If exactly pig $0$ and $1$ die, this has the poison.

- Bucket $7 = 111_{2}$: Give this bucket to all pigs. If all pigs die, this has the poison.

We can see now, that for $r = 1$, we can succeed with $k = \lceil \log_2 n \rceil$ pigs, as that’s how many bit positions we need to represent $n$ different numbers in binary.

Now, what do we do, when we have more than one round to test, how does this setup change?

After the first round of testing, some pigs will stay alive, so we can use them for the next round. Each pig may only die in exactly one round. If we record our results, we may write down the number of the round that the pig died in, denoting with $0$ the pigs, that are still alive at the end.

So this means that our resulting pattern is now an base-$(r+1)$ number and we can apply the same logic as before.

For example:

Let’s say we have $2$ rounds and $8$ buckets. For this, we will need $2$ pigs.

Let’s index the buckets between $0$ and $7$, and convert them to base-$3$!

- Bucket $0 = 00_3$: Don’t give this bucket to any pigs.

- Bucket $1 = 01_3$: Give this to pig $0$ in round $1$.

- Bucket $2 = 02_3$: Give this to pig $0$ in round $2$.

- Bucket $3 = 10_3$: Give this to pig $1$ in round $1$.

- Bucket $4 = 11_3$: Give this to both pigs in the first round.

- Bucket $5 = 12_3$: Give this to pig $1$ in round $1$ and pig $0$ in round $2$.

- Bucket $6 = 20_3$: Give this to pig $1$ in round $2$.

- Bucket $7 = 21_3$: Give this to pig $1$ in round $2$ and pig $0$ in round $1$.

Since all patterns are different, we can tell from the result which was the poisonous bucket.

Therefore, we can succeed using $k = \lceil \log_{r+1} n \rceil$ pigs in general.

We currently don’t have a rigorous proof on the lower bound of this, but intuitively you can see that an argument similar to the lower bound on comparison-based sorts could be established.

Finally, the code to calculate the formula above:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

class Solution

{

public:

int poorPigs(int buckets, int minutesToDie, int minutesToTest)

{

int rounds=minutesToTest/minutesToDie;

int pigs = 0;

int maxbuckets = 1;

while(maxbuckets < buckets)

{

maxbuckets *= (rounds + 1);

++pigs;

}

return pigs;

}

};

We did a linear search for the first exponent of $(r + 1)$ which is larger than or equal to $\text{buckets}$. This runs in logarithmic time relative to $n$, so it’s actually pretty fast.

Note here, that although it may be compelling to use code similar to this instead, it results in a Wrong Answer:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

class Solution

{

public:

int poorPigs(int buckets, int minutesToDie, int minutesToTest)

{

int rounds = minutesToTest/minutesToDie;

return ceil(log(buckets) / log(rounds+1));

}

};

This is due to problems with floating point precision. For example, for rounds=4 and buckets=125, the correct answer is $3$, but the resulting numbers are just slightly off.

1

2

3

log(buckets) = 4.82831373730230151153364204219542443752288818359375

log(rounds+1) = 1.6094379124341002817999424223671667277812957763671875

result = 3.000000000000000444089209850062616169452667236328125

I bet the testcases were designed intentionally to fail this type of submission.

Although we can employ tricks like substracting some $\varepsilon$ value before the ceil is applied, but a good rule of thumb for competitive programming is to avoid floating point numbers at all costs, so it is best to stick with the integer-only solutions whenever we can.